Beyond the Grade: Unpacking the Logic of Little Johnny and the Crisis of Early Mathematics Education

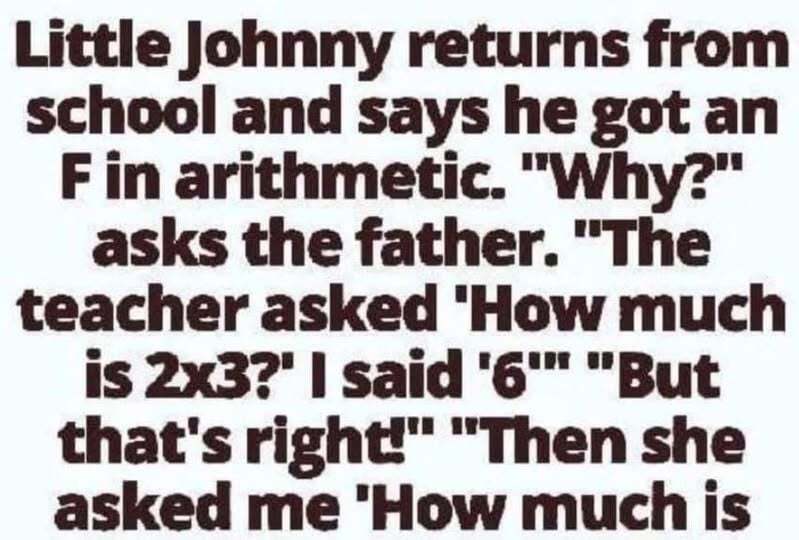

Mathematics is often described as the universal language, a world of absolute truths and immutable laws. Yet, for many children entering the formal education system, it feels less like a language and more like an arbitrary set of hurdles. The story of “Little Johnny,” a student who received an “F” for what he perceived as a common-sense answer, is more than a humorous anecdote. It is a window into the psychological friction that occurs when a child’s intuitive logic meets the rigid structures of traditional pedagogy.

At its core, Johnny’s story highlights a critical divide in modern education: the struggle between rote memorization (learning “what”) and conceptual understanding (learning “why”). By examining the classroom interaction that led to his failing grade, we can uncover profound insights into how we teach, how children learn, and why the “wrong” answer is sometimes the most logical one.

Part I: The Classroom Incident—The Clash of Order and Logic

The scenario was deceptively simple. In a foundational multiplication lesson, the teacher posed two questions to the class. The first: “What is three times two?” Johnny answered correctly: “Six.” The second: “What is two times three?” To an adult or a mathematician, these are identical expressions of the same product. However, in an elementary classroom, these questions are often used to test a student’s grasp of grouping and arrays.

The Teacher’s Perspective

From a pedagogical standpoint, the teacher may have been looking for an understanding of the Commutative Property of Multiplication. This property states that $a \times b = b \times a$. While the result is the same, the conceptual model changes:

-

$3 \times 2$ is often visualized as three groups of two.

-

$2 \times 3$ is visualized as two groups of three.

If a teacher is strictly adhering to a curriculum that rewards the specific visualization over the numerical result, a student who sees the two as redundant might be labeled as “failing” to grasp the lesson’s nuance.

Johnny’s Intuitive Logic

Johnny’s response to his father—“That’s what I said!”—reveals a high level of intuitive mathematical thinking. He recognized the symmetry of multiplication. To him, the teacher’s second question felt like a trick or a waste of time. When his father reacted with, “What’s the difference?” he was validating a mathematical truth that the educational system often obscures in its early stages: the order of factors in multiplication does not change the product.

Part II: The Psychology of the “F”—Grades as Barriers to Learning

Receiving a failing grade at a young age can have a “scarring” effect on a student’s relationship with a subject. Educational psychologists often point to Math Anxiety as a learned response to early failures that felt unfair or nonsensical.

The Impact of Achievement Emotions

Research into “achievement emotions” suggests that students who experience early success (pride and enjoyment) develop a “growth mindset.” Conversely, students like Johnny, who feel they have given a correct answer but are punished for it, may develop “aversion.“

-

Cognitive Dissonance: Johnny knew $3 \times 2 = 6$. He knew $2 \times 3 = 6$. Being told he was “wrong” creates a mental conflict that can lead to a student disengaging from the subject entirely.

-

The Weight of the Red Pen: An “F” suggests a total lack of understanding. In Johnny’s case, it wasn’t a lack of understanding; it was a lack of compliance with a specific, rigid teaching method.

Rote Learning vs. Conceptual Understanding

The “F” in this story is a symptom of a larger systemic issue: the over-reliance on rote learning.

-

Rote Learning: Students are taught to memorize the “times tables” as if they were a list of dates or spelling words.

-

Conceptual Learning: Students are taught the meaning of the numbers—how they represent objects in space and relationships between groups.

Johnny actually demonstrated a strong conceptual grasp of multiplication (the “switcheroo” or commutative property), yet the grading system penalized him because it was likely focused on the procedural step of following the teacher’s specific sequence.

Part III: The Role of the Parent—Bridging the Gap

The father’s reaction in the story is equally telling. His frustration—“What’s the difference?”—is the voice of the real world. In professional fields, from engineering to accounting, the commutative property is a tool for efficiency, not a point of contention.

Validating the Child’s Thought Process

The most important thing a parent can do in this situation is what Johnny’s father did: validate the logic. By agreeing that “six is six,” the father protected Johnny’s confidence.

-

The Home-School Bridge: When parents and teachers aren’t on the same page regarding “modern math” or specific teaching techniques, the child often becomes the casualty.

-

Judgement-Free Conversations: Opening a dialogue with the child about how they reached an answer is more valuable than focusing on whether the answer matched the teacher’s key.

Strategies for Supporting “Johnnys”

-

Use Manipulatives: Use blocks or coins to show the child that three groups of two is physically the same total as two groups of three. This bridges the gap between the teacher’s “order” and the child’s “result.“

-

Focus on the “Why”: Ask the child, “Why do you think the teacher asked the second question?” This helps them develop meta-cognition—thinking about the thinking of others.

-

Advocacy: Parents should feel empowered to discuss these “logical failures” with teachers, ensuring that a child’s natural mathematical intuition isn’t snuffed out by a rigid grading rubric.

Part IV: Broadening the Context—The Future of Math Education

The story of Little Johnny reflects a global debate about how to prepare students for the 21st century. In an era of calculators and AI, the ability to memorize $6 \times 7 = 42$ is less important than the ability to understand systemic relationships.

The “New Math” Struggle

Many parents struggle with “Common Core” or “New Math” because it asks students to show multiple ways of arriving at an answer. While the goal—deeper conceptual understanding—is noble, the implementation often leads to situations where a child who gets the “right” answer via a “wrong” method is penalized.

Resilience in the Face of Failure

Ultimately, Johnny’s story is one of resilience. He didn’t come home crying; he came home puzzled. His ability to maintain his humor and his conviction in his own logic is a trait that will serve him well in higher-level mathematics, where “common sense” and the ability to challenge assumptions are the hallmarks of a great thinker.

Conclusion: The Final Verdict

Little Johnny didn’t “fail” math. The “F” on his paper was a failure of a specific educational moment to recognize a burgeoning mathematical mind. If we want to foster a generation of problem-solvers, we must move away from a culture of “compliance” in the classroom and toward a culture of “curiosity.“

When a child tells us $3 \times 2$ is the same as $2 \times 3$, we shouldn’t ask for a different answer. We should celebrate that they have discovered a fundamental law of the universe—and then, perhaps, ask them to show us how they’d prove it with a handful of marbles.