The Science of Longevity: How Blood Biomarkers and Genetics Predict the Journey to 100

In the early 20th century, reaching the age of 100 was considered a statistical anomaly—a rare feat of nature that made headlines. Today, however, centenarians represent one of the fastest-growing demographic groups in the developed world. This shift has prompted a profound question within the medical community: Is extreme longevity a matter of lifestyle, sheer luck, or is it written in our biology?

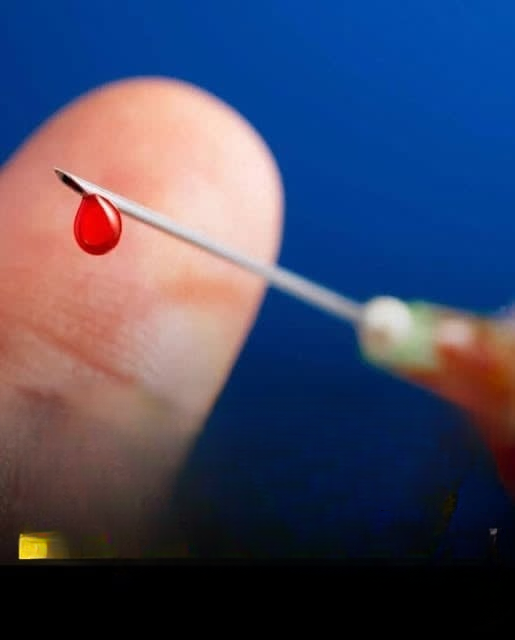

Recent longitudinal research, particularly out of Sweden, has provided some of the most compelling evidence to date. By analyzing the “biological footprints” left in blood tests decades before a person reaches old age, researchers are beginning to decode the internal conditions necessary for a human to survive a full century. This article explores the relationship between blood biomarkers, genetics, and the pursuit of the “century mark.”

I. The AMORIS Study: A Landmark in Longevity Research

To understand how blood markers relate to lifespan, researchers utilized the AMORIS cohort (Apolipoprotein-related MOrtality RISk), a massive population-based study from Stockholm County.

1. Scope and Methodology

The study followed over 44,000 Swedish participants born between 1893 and 1920. These individuals underwent routine blood testing between 1985 and 1996, when they were generally in their 60s or 70s. The researchers then tracked these individuals for up to 35 years using Sweden’s highly accurate national registers.

2. The Centenarian Milestone

Out of the initial cohort, 1,224 participants (approximately 2.7%) reached their 100th birthday. Interestingly, 85% of these centenarians were women. The primary goal was to see if the blood profiles of those who lived to 100 differed significantly from their peers who passed away earlier.

II. Key Biomarkers: The “Signature” of the Long-Lived

The research focused on 12 specific biomarkers related to inflammation, metabolism, liver and kidney function, and potential anemia. The results showed that, starting as early as age 65, the blood profiles of future centenarians began to diverge from those of their shorter-lived counterparts.

1. Glucose and Metabolic Efficiency

One of the strongest indicators of longevity was blood glucose levels. Those who reached 100 rarely had glucose levels in the highest percentiles during their 70s. High glucose is a precursor to type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, both of which accelerate cellular aging.

2. Kidney Function (Creatinine)

Creatinine is a waste product filtered by the kidneys. Future centenarians consistently showed lower, more stable creatinine levels. This suggests that maintaining high-functioning renal filtration is essential for clearing toxins and maintaining the body’s chemical balance over many decades.

3. Inflammation Markers (Urate)

Uric acid (urate) is a marker often tied to inflammation and oxidative stress. The study found that individuals with the lowest urate levels had a significantly higher chance of reaching age 100. High urate is often linked to gout and cardiovascular issues, suggesting that “low-inflammation” bodies are better suited for long-term survival.

III. The Role of Blood Type in Longevity

While the AMORIS study focused on metabolic markers, broader genetic research has frequently looked at the ABO blood group system as a factor in lifespan.

1. The “Type O” Advantage?

Several international studies have suggested that individuals with Blood Type O may have a slight statistical advantage in longevity. This is largely attributed to lower levels of certain clotting factors, which may reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and thromboembolism.

2. Type B and Healthy Aging

In some centenarian-dense regions (often called “Blue Zones”), researchers have noted a higher prevalence of Type B individuals among those reaching 100. While the reasons are still being studied, it is hypothesized that certain blood types may offer better resistance to specific environmental pathogens or chronic inflammatory triggers.

IV. The Biological Resilience Factor

What the Swedish study ultimately reveals is the concept of biological resilience. Centenarians do not necessarily lack “bad” genes; rather, their bodies appear to maintain homeostatic balance more effectively.

-

Liver Health: Markers like GGT (gamma-glutamyl transferase) remained lower in centenarians, indicating a robust ability to process environmental toxins.

-

Iron Status: Healthy iron levels (Total Iron Binding Capacity) were found to be crucial. Both extreme iron deficiency and iron overload are associated with decreased lifespan.

V. Can We Influence Our Biomarkers?

The most encouraging takeaway from this research is that while genetics play a role, many of the biomarkers identified—glucose, cholesterol, and inflammation—are heavily influenced by lifestyle.

-

Metabolic Management: Reducing refined sugar intake and maintaining physical activity can keep glucose and creatinine in the “longevity zone.”

-

Anti-Inflammatory Living: Diets rich in antioxidants (like the Mediterranean or DASH diets) help keep urate levels low.

-

Routine Monitoring: Regular blood tests aren’t just for diagnosing illness; they provide a “map” of how well your body is aging.

Conclusion: The Path to 100

The Swedish study proves that extreme longevity is rarely an accident. It is the result of a body that maintains “biomarker stability” over decades. While we cannot change our blood type, we can monitor the metabolic and inflammatory markers that indicate how our internal systems are coping with the passage of time.

Reaching 100 is a marathon of biological efficiency. By understanding these blood markers today, we can make informed choices to ensure that our later years are not just long, but vibrant and healthy.