The Silent Fractures: Navigating Arizona’s Groundwater Crisis and the Rise of Earth Fissures

Arizona is a land of profound contrasts. From the towering pines of the Mogollon Rim to the sun-drenched expanses of the Sonoran Desert, it is a state defined by its rugged beauty and an incredible spirit of growth. For decades, Arizona has been a beacon for development, drawing millions with the promise of wide-open spaces and a thriving economy.

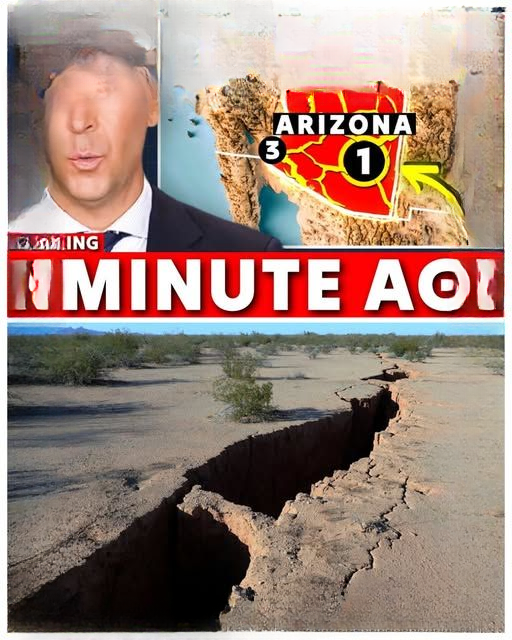

But beneath this success story, a slow-motion emergency is unfolding. While the surface reflects a modern, bustling civilization, the subterranean reality is far more fragile. The state’s aquifers—natural underground reservoirs that have sustained life in the desert for millennia—are being depleted at an unsustainable rate. The physical consequence of this depletion is the emergence of earth fissures: jagged, miles-long scars that represent a literal breaking point for the desert floor.

1. The Science of Subsidence: Why the Earth is Splitting

To understand the cracks on the surface, one must look hundreds of feet below ground. Most of Arizona’s desert basins are filled with layers of alluvium—sediment consisting of gravel, sand, and clay. Interspersed within these layers are vast quantities of groundwater.

The Role of Pore Pressure

In a healthy aquifer, water occupies the spaces (pores) between sediment grains. This water provides internal pressure that helps support the weight of the soil above. When groundwater is pumped out faster than it can be recharged by rainfall or snowmelt, that internal support vanishes.

Permanent Compaction

Once the water is removed, the sediment grains collapse and pack more tightly together. This process, known as aquifer compaction, causes the land surface to sink—a phenomenon called land subsidence. While subsidence can be gradual and widespread, it becomes catastrophic when it occurs unevenly.

The Birth of a Fissure

When one area sinks faster than an adjacent area (often due to varying soil compositions or underlying bedrock), the tension becomes too great for the dry earth to bear. The ground snaps, creating a vertical crack. These fissures often start as narrow, nearly invisible threads, but during monsoon rains, water rushes into them, eroding the sidewalls and causing them to expand into massive chasms that can be dozens of feet deep and miles long.

2. A Legacy of “Borrowed” Water

Arizona’s water history is a masterclass in engineering and ambition. The creation of the Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal system brought Colorado River water to the deserts, fueling the boom of cities like Phoenix and Tucson. However, rural areas and many agricultural hubs remain almost entirely dependent on groundwater.

For over a century, the mindset was one of abundance. Farmers transformed the arid landscape into a powerhouse of cotton, alfalfa, and citrus production. Later, developers saw the same land as the perfect site for sprawling master-planned communities.

The “slow emergency” cited by geologists stems from the fact that groundwater is often “fossil water”—water that entered the ground thousands of years ago during a much wetter climatic era. When we pump this water today, we are effectively “mining” a non-renewable resource. Once the pore spaces collapse and the fissures form, the aquifer loses its capacity to hold water forever. Even if the state experienced record-breaking rainfall, the ground has lost its “sponge-like” quality.

3. The Socio-Economic Impact: Living on Shifting Ground

The emergence of earth fissures is not merely a geological curiosity; it is a direct threat to the infrastructure of modern life. Unlike earthquakes, which are sudden and violent, fissures are a persistent, creeping liability.

Infrastructure and Utilities

Fissures do not respect property lines or engineering plans. They have been known to:

-

Sever Utility Lines: As the ground shifts, buried water, gas, and sewer lines can snap, leading to service interruptions and expensive repairs.

-

Destabilize Highways: State transportation departments must constantly monitor “subsidence zones” where roads may buckle or crack, creating hazards for motorists.

-

Impact Rail and Canals: Linear infrastructure is particularly vulnerable. Even a slight tilt in a canal’s gradient due to subsidence can disrupt the flow of water, costing millions in re-engineering.

The Real Estate Dilemma

For homeowners, a fissure discovered near or under a property can be devastating. In many cases, these geological features are not covered by standard homeowners’ insurance. As awareness grows, the “honest acknowledgment” of risk becomes a point of contention. Should developers be allowed to build in known subsidence zones? How much disclosure is required when a crack opens up in a backyard?

4. Policy at a Crossroads: The Search for Solutions

Arizona has long been a leader in water management, notably through the 1980 Groundwater Management Act. This landmark legislation created Active Management Areas (AMAs) where groundwater pumping is strictly regulated to achieve “safe yield.”

However, many of the most severe fissures are appearing outside of these protected zones. In rural counties where “wildcat” pumping remains largely unregulated, massive corporate farms and new housing developments are tapping into the same shrinking pools of water.

Potential Paths Forward:

-

Expanded Regulation: Expanding the AMA boundaries to include at-risk rural basins.

-

Managed Aquifer Recharge: Using treated wastewater or excess surface water to “recharge” aquifers, though this is only possible in areas where compaction hasn’t already occurred.

-

Advanced Mapping: The Arizona Geological Survey (AZGS) continues to map these fissures using satellite technology (InSAR). Public access to these maps is crucial for informed urban planning.

5. Conclusion: A Call for Adaptation

The jagged scars across the Arizona desert are a physical manifestation of a policy imbalance. They remind us that the desert has limits, and that growth cannot be decoupled from hydrological reality.

To ensure that Arizona’s communities endure, the state must move beyond the era of “borrowed ground.” This requires a shift from exploitation to stewardship. By integrating geological data into urban planning and strengthening groundwater protections, Arizona can mitigate the risks of a shifting landscape. The cracks in the earth are a warning, but they also offer an opportunity to build a more resilient and sustainable future for the American West.