On January 1, New York City is expected to enter a new era. Zohran Mamdani, following a decisive election victory, is scheduled to take the oath of office and assume leadership of the largest city in the United States. If everything proceeds according to plan, he will become the next mayor of New York City—marking a historic moment for the city on multiple levels.

Yet alongside the preparations, celebrations, and political transition, an unexpected academic debate has emerged. At its center is not Mamdani’s platform, policies, or political ideology, but rather a surprisingly technical question: What number mayor will he actually be?

This question, rooted in colonial-era recordkeeping and centuries-old documentation, has drawn attention from historians, archivists, and city officials alike. While it does not threaten the legitimacy of the election or Mamdani’s ability to govern, it raises a fascinating issue about how history is recorded—and occasionally miscounted.

A Historic Election With Widespread Attention

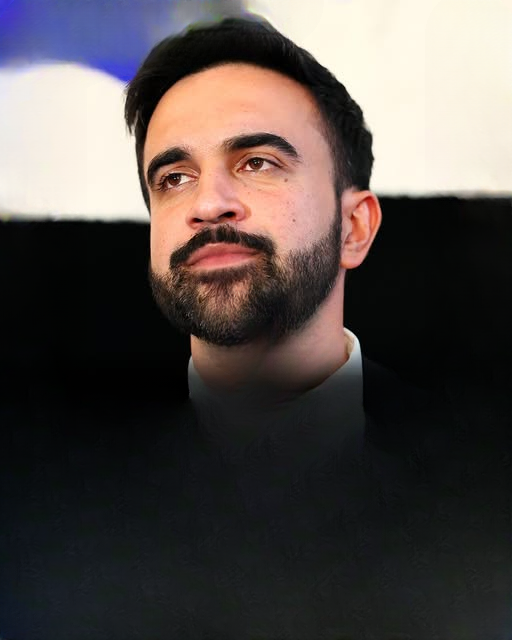

The most recent New York City mayoral election captured national and international interest. With high voter turnout and intense public engagement, the race became one of the most closely followed local elections in decades.

Zohran Mamdani emerged victorious with a commanding share of the vote, earning just over half of all ballots cast. His margin of victory placed him comfortably ahead of his opponents, including Republican candidate Curtis Sliwa and independent contender Andrew Cuomo, a former governor of New York.

Election analysts noted that Mamdani’s success was driven by strong participation from younger voters, as well as support from communities energized by his grassroots organizing and policy proposals. The outcome represented a clear decision by voters rather than a narrow or contested result.

The election, held on November 4, also set a turnout record for New York City mayoral races not seen since the early 1990s. Many observers attributed this surge in participation to heightened political engagement nationwide, as well as the visibility of the candidates involved.

Global Reactions and Political Context

News of Mamdani’s victory quickly traveled beyond city limits. International media outlets covered the results, particularly highlighting the broader political implications.

Some prominent national figures expressed criticism or concern over the outcome, while others framed it as evidence of shifting political dynamics in urban America. Regardless of interpretation, the election became part of a larger conversation about the future direction of U.S. cities and the balance between progressive and conservative approaches to governance.

What remained consistent across coverage, however, was acknowledgment of the election’s significance.

Breaking Barriers and Setting Records

If sworn in as planned, Zohran Mamdani will reach several historic milestones.

He is set to become:

-

The first Muslim mayor in New York City’s history

-

One of the youngest individuals ever elected to the office, assuming the role at age 34

-

A leader emerging from a background in community organizing rather than traditional political pathways

These factors have made his ascent particularly noteworthy in a city shaped by immigration, diversity, and political evolution.

For many supporters, Mamdani’s election symbolizes inclusion and generational change. For others, it represents a broader ideological shift. From a historical standpoint, it adds another distinctive chapter to New York City’s long and complex civic story.

From Community Organizing to City Hall

Mamdani’s rise did not follow the conventional trajectory often associated with mayoral candidates.

Before entering citywide politics, he worked as a community organizer in Queens, focusing on housing issues, public services, and tenant advocacy. His early efforts centered on local engagement rather than high-profile political positioning.

In 2020, he was elected to the New York State Assembly, where he gained experience in legislative processes and built a public profile grounded in policy advocacy.

This background shaped his mayoral campaign, which emphasized direct outreach, neighborhood-level organizing, and clear policy messaging. His campaign style resonated with voters seeking a departure from traditional political norms.

Preparing for the Transition of Power

With the election decided, preparations are underway for the transition from outgoing mayor Eric Adams to the incoming administration.

Transition teams are reviewing city operations, setting policy priorities, and coordinating with municipal departments to ensure continuity of services. These efforts are standard practice and designed to provide stability during leadership changes.

Amid these preparations, attention typically focuses on logistics, staffing, and agenda-setting. However, this transition period has also brought renewed interest in a lesser-known aspect of city governance: the official historical record of New York City’s mayors.

An Unexpected Historical Question Emerges

As Mamdani prepares to take office, historian Paul Hortenstine has raised an intriguing claim that challenges a long-accepted detail of New York City history.

According to Hortenstine, the city’s official count of its mayors may be incorrect.

Specifically, he argues that a mayoral term from the 17th century was omitted from official records—a mistake that has been repeated for nearly two centuries. If his research is accurate, the numerical designation traditionally assigned to each mayor is off by one.

This means that Mamdani, commonly described as the city’s 111th mayor, would technically be the 112th.

The Origins of the Claim

Hortenstine’s research did not begin as an attempt to recount mayors. Instead, he was studying early New York City governance and its connections to broader colonial systems, including trade networks and political appointments.

While examining historical documents from the colonial period, he came across papers associated with Edmund Andros, who served as governor of New York in the 1670s.

Within those documents, Hortenstine identified evidence suggesting that Mayor Matthias Nicolls served an additional, nonconsecutive term that is not reflected in the city’s official mayoral list.

Why One Missing Term Matters

In modern recordkeeping, nonconsecutive terms are counted separately. For example, when an individual serves in office, leaves, and later returns, each term is recognized as distinct.

This principle applies at all levels of government. A widely known example is the presidency of the United States, where nonconsecutive terms are numbered separately.

If the same standard is applied retroactively to New York City’s early mayors, then omitting one term would shift the numbering of every mayor who followed.

A Mistake Passed Down Through Time

According to Hortenstine and earlier historian Peter R. Christoph, who noted the same issue in 1989, the error appears to have originated in the 19th century.

They suggest that an 1841 municipal manual failed to include Nicolls’ second term. Subsequent publications relied on that manual as a reference, repeating the omission in later records.

Over time, the incorrect count became accepted as fact.

Reaction From City Officials and Archivists

City officials have acknowledged awareness of the research. Representatives from the Department of Records have confirmed that historians have raised questions about the accuracy of the mayoral list.

Ken Cobb, an assistant commissioner with the department, described the issue as a legitimate historical inquiry, noting that discrepancies can arise when working with records dating back hundreds of years.

While no immediate changes have been announced, the city has not dismissed the claim outright.

What This Means for the Inauguration

Importantly, this historical debate does not affect the legality of Mamdani’s election or his ability to serve as mayor.

Regardless of whether he is labeled the 111th or 112th mayor, his authority comes from the voters and the city’s legal framework, not from numerical designation.

However, should the research gain official acceptance, it could prompt revisions to:

-

Inauguration materials

-

Official biographies

-

Educational resources

-

Historical plaques and archives

Such updates would be largely symbolic but meaningful to historians and archivists.

Why Historical Accuracy Still Matters

Some may wonder why this issue deserves attention at all.

The answer lies in how cities understand their own histories. Accurate records help preserve institutional memory, inform education, and provide context for civic identity.

New York City, with its long and complex past, has always placed importance on historical documentation. Revisiting old records is part of maintaining that tradition.

A Reminder That History Is Not Static

This debate serves as a reminder that history is not frozen in time. New discoveries, reinterpretations, and corrections occur regularly as scholars examine primary sources with fresh perspectives.

Even well-established facts can be reconsidered when new evidence emerges.

In this case, the discussion does not diminish the significance of Mamdani’s election. Instead, it adds an unexpected layer to an already notable moment.

The Bigger Picture

As January 1 approaches, public attention will rightly focus on policy priorities, leadership style, and the challenges facing New York City.

The question of mayoral numbering, while intriguing, remains secondary to the practical realities of governing a city of more than eight million people.

Still, it highlights how the past and present often intersect in unexpected ways.

A Milestone Regardless of the Number

Whether officially recorded as the 111th or 112th mayor, Zohran Mamdani’s inauguration will mark a turning point for New York City.

His election reflects voter engagement, demographic change, and evolving political values. The historical footnote surrounding his mayoral number does not overshadow those achievements—it simply enriches the story.

Conclusion: When the Past Meets the Present

On the day Mamdani takes the oath of office, the focus will be on the future: housing, transportation, public safety, education, and economic opportunity.

Yet somewhere in the city’s archives, centuries-old documents will quietly remind observers that even the most modern political moments are built upon layers of history.

Sometimes, those layers reveal surprises.

And sometimes, they remind us that history—like democracy—is an ongoing process of discovery, correction, and renewal.