Introduction: Shadows Beneath the Southern Sun

In the heart of Burke County, Georgia, the land tells stories few dare to hear. The red clay soil, the winding rivers, and the towering pines hold more than the memory of a Southern landscape—they hold secrets of human lives shaped by power, oppression, and resilience. While the antebellum era’s grandeur is often romanticized in textbooks and heritage tours, buried beneath the moss-draped oaks are truths that challenge our understanding of morality, society, and legacy.

One of these truths centers on Thornhill Estate, a plantation that once stretched across fertile fields and cotton-laden hills. Today, its buildings lie in ruin, its ledgers lost or destroyed, yet its imprint on local history and human experience remains profound. The story of Thornhill is not just about slavery, rebellion, or the Civil War. It is a study of power, control, and moral responsibility—a reminder that even when physical structures vanish, human legacies endure.

The Rise of Thornhill Estate

Georgia’s Agricultural Backbone

In the years leading up to the Civil War, Georgia’s economy was dominated by plantations producing cotton, tobacco, and rice. Burke County, with its rich soil and access to trading routes, became home to numerous estates, large and small, each shaping the social hierarchy of the region. Thornhill Estate was among these, occupying both a physical and symbolic place in the fabric of Southern life.

Initially, Thornhill was a thriving plantation, its fields abundant and its management attentive. The estate’s prominence, however, was closely tied to the fortunes—and misfortunes—of its owners. Katherine Danforth Thornhill, a young widow who inherited the estate following her husband’s death, faced challenges that tested her intellect, resilience, and moral compass. She inherited not only land and crops but also debt, societal expectations, and the labor systems of a rapidly changing South.

Crisis and Radical Experiments

Katherine’s tenure at Thornhill was marked by desperation and innovation, but also moral ambiguity. Faced with economic pressures and a fragile labor system, she implemented a series of strategies aimed at consolidating control over the estate and its people. Letters, journals, and oral histories suggest that Thornhill became more than a plantation—it became a carefully managed social ecosystem.

Rather than relying solely on conventional labor arrangements, Katherine appeared to view the estate as an experiment in social engineering. Those who worked on Thornhill were constrained not just by legal obligations but by psychological and ideological frameworks, a system designed to maintain loyalty, obedience, and social order. While details remain fragmentary, the legacy of these practices left enduring marks on families and communities, shaping local memory for generations.

Unearthing the Past: Reconstructing Thornhill

Union Troops and the First Glimpses

In 1864, the Union Army’s 34th Massachusetts Infantry passed through Georgia as part of the campaign to dismantle Confederate strongholds. Among the sparse mentions of Thornhill in soldiers’ letters, one finds references to “peculiar households” and a labor force bound by more than mere contracts. These brief observations became vital clues, forming the foundation for historians’ later reconstructions.

By comparing these military records with property maps, census fragments, family memoirs, and oral histories, researchers began to assemble a picture of Thornhill that had long been obscured. While the documentation was incomplete, the patterns were clear: Thornhill operated under social rules that extended beyond conventional hierarchies, creating a controlled environment with profound human consequences.

Oral Traditions: Memory as Resistance

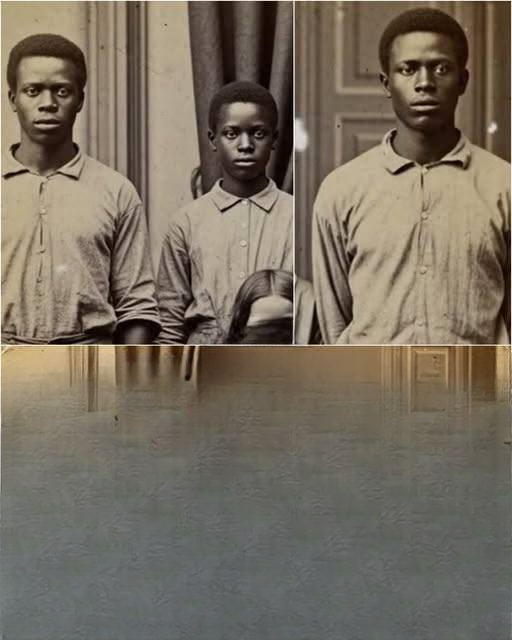

For Black communities surrounding Thornhill, stories of the estate were preserved in memory, passed down through generations. Elders recounted life on the plantation not as a tale of grandeur but as an enduring lesson in resilience, endurance, and moral strength. References to “the old place” or “the house that wasn’t quite free” reveal lives lived under constraint yet suffused with human agency.

These oral histories provide moral context often absent from official records. They describe acts of resistance, subtle forms of defiance, and the cultivation of dignity despite systemic oppression. Though details sometimes conflict, they consistently emphasize one reality: the people of Thornhill were subject to invisible forces designed to govern their behavior, yet they found ways to assert autonomy, build community, and safeguard memory.

Archival Puzzles and Genealogical Discoveries

From the 1970s onward, historian Rebecca Hollis undertook meticulous research on overlooked Civil War-era sites in Georgia, including Thornhill. Her work involved cross-referencing property maps, probate records, tax ledgers, and surviving family journals. Hollis discovered evidence of deliberate erasure: missing documents, altered entries, and other forms of historical manipulation, suggesting an intentional effort to obscure Thornhill’s reality.

Modern genealogical techniques, including DNA analysis, have connected living descendants to both the Thornhill family and those who labored on the estate. These discoveries have proven deeply emotional, exposing hidden truths and fostering new dialogues about legacy, responsibility, and the ways personal histories intersect with national narratives.

The Social Engineering of Thornhill

Power as a System

Katherine Thornhill’s approach to estate management reflected a larger belief in controlling human behavior through structured environments. References to a “loyal household” and “self-perpetuating labor” suggest that she viewed Thornhill as a microcosm of social order—an experiment in shaping individuals and families according to her vision.

Workers were not merely employees; they were participants in a system designed to limit autonomy and enforce obedience. Surveillance, emotional coercion, and rigid hierarchies were tools to maintain the estate’s internal equilibrium. Children grew up internalizing these rules, their experiences dictated by proximity to power rather than freedom of choice.

Surveillance, Division, and Psychological Control

Accounts of life at Thornhill depict a network of constant observation. Relationships—romantic, familial, and social—were tightly controlled. Some oral histories report children being relocated at the discretion of the mistress, demonstrating the extent to which personal freedoms were subordinated to the estate’s objectives.

This system created tension between conformity and self-determination. The line between protection and coercion blurred, leaving workers in a perpetual state of negotiation with authority. Thornhill was not simply a plantation; it was an apparatus of psychological and social control.

Resistance and the Long Road to Freedom

Emancipation offered liberation for many Thornhill residents, but it was neither immediate nor absolute. Some fled north or west, seeking new lives. Others stayed, forming communities, churches, schools, and networks of mutual aid. These actions preserved memory, transmitted resilience, and established frameworks for survival beyond the plantation system.

Destruction of ledgers and records—whether by former workers or subsequent caretakers—symbolized both freedom and the collapse of an oppressive order. These acts of erasure, while practical, also carried moral significance, severing the estate’s ability to enforce control through documentation.

Thornhill and the Civil War

The Arrival of Union Forces

By 1864, the tide of war had reached Georgia. Union troops found Thornhill largely abandoned: its workforce dispersed, its mistress absent or concealed, and its fields no longer productive. Soldiers’ observations, though sparse, highlight the estate’s uniqueness, a site caught between decline and the forces of historical change.

Local memory recounts symbolic acts of resistance: burning records, dismantling buildings, and reclaiming agency. Thornhill’s collapse was not only physical but social, an unrecorded revolution in the everyday lives of its inhabitants.

Postwar Abandonment

After the Civil War, Thornhill faded from maps and county registries. Its structures deteriorated, and the land slowly reverted to forest. The narrative of emancipation often bypassed estates like Thornhill, favoring broader tales of Reconstruction or the Lost Cause. Yet for descendants, both Black and white, memory preserved the lessons of survival, resistance, and the moral consequences of power.

Rediscovery and Moral Reckoning

Dr. Hollis’ Research

Dr. Rebecca Hollis’ work brought Thornhill back into focus. She identified gaps, erasures, and intentional obfuscations in local records, arguing that a culture of forgetting had been cultivated to protect reputations and sanitize Southern memory. Her research underscores the danger of invisibility: without acknowledgment, injustice persists, and moral lessons are lost.

Genealogical Connections

Modern genealogical work has linked descendants across racial lines, revealing intertwined histories shaped by Thornhill. Families confronted painful truths: children moved without consent, labor exploited, lives constrained. These revelations prompted reflection, dialogue, and, in some cases, reconciliation. Thornhill’s history is a living lesson in understanding heritage and accepting moral responsibility.

Lessons from Thornhill

Hidden Systems of Power

Thornhill demonstrates that oppression does not always announce itself through brutality. Often, it operates subtly, normalized within social structures, disguised by respectability or tradition. Recognizing these patterns is essential for understanding how historical injustices reverberate into the present.

Accountability and Memory

Erasure—whether through burned documents, missing records, or deliberate omission—prevents justice and complicates societal understanding. Thornhill illustrates that forgetting can perpetuate harm as much as overt oppression. Restoring memory and recounting suppressed histories is a form of moral repair.

The Role of Storytelling

Recovering Thornhill’s story is not about sensationalism; it is about truth, empathy, and responsibility. By listening to oral tradition, cross-referencing archival evidence, and embracing complexity, we honor lives once silenced. Education and remembrance become acts of ethical engagement, transforming historical knowledge into contemporary awareness.

Inheritance and Responsibility

Today, many social, economic, and political structures trace their roots to historical systems like Thornhill. Confronting this legacy invites questions: What responsibilities accompany inherited privilege? How can society address past harm and prevent its perpetuation? Thornhill challenges us to confront uncomfortable truths while imagining a more just future.

Conclusion: Reckoning, Reflection, and the Living Legacy

The physical estate of Thornhill no longer exists. No plaque, marker, or museum preserves its memory. Yet its story endures in the minds of descendants, the moral fabric of the region, and the ongoing dialogue about history, justice, and identity.

The lessons of Thornhill are timeless: history cannot be understood merely by forgetting unpleasant truths. Moral courage requires examining past injustices, acknowledging human resilience and suffering, and allowing these lessons to shape our present and future.

Thornhill Estate is not a relic of the past. It is an invitation—a call to reckon with history, grieve with empathy, and engage with the moral questions that continue to echo from the red clay of Burke County. By listening, reflecting, and acting, we ensure that silence does not outlast justice, and that the buried legacies of the Deep South can finally be brought to light.