The winter of 1842 in Charleston, South Carolina, was harsh — a biting cold that seeped into the grand houses of the city and whispered along the corridors of Charleston’s most esteemed residences. It was the kind of winter that made old walls remember things best left forgotten, secrets tucked beneath layers of paint and polished wood. For the Caldwell family, it would become a winter that revealed both heartbreak and scandal, one that would haunt Charleston for decades to come.

A Widow in the Shadows

Mrs. Josephine Caldwell, recently widowed, was still draped in mourning when the first hints of scandal appeared. Her husband, Howard Caldwell, had been one of Charleston’s wealthiest shipping magnates, his life and death a subject of fascination among the city’s elite. Howard’s sudden demise at his desk, ruled a heart seizure by physicians, left Josephine in profound grief. She sealed his study immediately after the funeral and withdrew from society, abandoning the social gaiety that had once defined her presence. Her laughter disappeared entirely, leaving the stately Caldwell residence on Church Street in a silence broken only by the crackling of the hearth.

The Caldwell home itself had long been an emblem of Charleston elegance. Its three stories of white columns, wrought-iron balconies, and manicured gardens reflected wealth, taste, and power. Yet behind that polished facade, grief and quiet obsession had begun to fester.

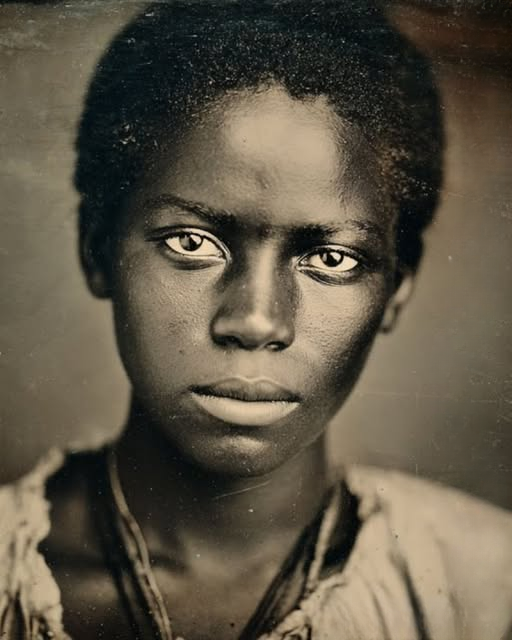

On December 17, 1842, Josephine shocked Charleston society by appearing at the slave auction on Market Street, a place she had never been seen before. The event was a recovery sale — the liquidation of Tobias Green’s debts through the sale of his remaining slaves. Among them was a frail young woman, barely able to stand, coughing violently and listed simply as Sarah, age 18, “damaged goods.”

Witnesses were puzzled when Josephine bid on her, purchasing the girl for only $18 — a fraction of the girl’s market value. Her coachman, Thomas Jenkins, recalled in his memoir years later:

“She clutched her bag as though it held her very heart. When the hammer fell, she looked at the girl not as property — but as if she’d seen a ghost.”

That night, Sarah was brought to the Caldwell home, marking the beginning of an unusual relationship that would soon uncover devastating truths.

A Girl With Familiar Eyes

Rather than placing Sarah in the servants’ quarters, Josephine ordered a small room prepared beside her own. Charleston society whispered about this unprecedented closeness — no lady of her standing would keep a slave so near, especially one so frail. Josephine tended to Sarah personally, feeding her broth, administering medicine, and watching over her with intense attention.

Friends and neighbors took note of Josephine’s unusual behavior. Eleanor Miller, a longtime friend, wrote in her diary:

“Josephine claims the girl’s eyes are familiar. She speaks of her as though she has known her all her life. I fear for my friend’s sanity.”

Weeks passed, and Josephine’s obsession only deepened. She taught Sarah household routines, the finer points of serving tea, reading ledgers, and accompanying her during quiet afternoons in the parlor. When questioned, Josephine would only say:

“She reminds me of someone I loved.”

The ambiguity of her words only fueled speculation. Was she haunted by memories of her husband, or was there a more direct connection to the girl herself?

The Night of the Ring

January 21, 1843, changed everything. A scream shattered the quiet of the Caldwell residence, piercing through the winter air. Harriet Davis, a maid, found Josephine standing over Sarah, who knelt amid shards of a broken teapot. Around the girl’s neck hung a gold signet ring engraved with the Caldwell family crest — the very ring believed to have been buried with Howard Caldwell.

The discovery struck Josephine like lightning. How could Sarah possess something that had been sealed with her husband in death? Her staff reported that she locked herself in her room for nearly a full day, emerging transformed, her grief morphing into resolve.

Flight and Confession

Two days later, Josephine summoned her solicitor and pastor. Together, they entered Howard’s sealed study, where his secrets had lain untouched since his death. The solicitor later recounted his shock:

“He looked as if he had seen death itself. He said only, ‘Some sins cannot be buried, no matter how deep the grave.’”

At dawn on January 25, Josephine and Sarah departed Charleston in secret, boarding a ship bound for Boston. A sealed letter was left with the coachman for Josephine’s sister, Margaret Rutledge, containing a single revelation:

“Sarah is Howard’s daughter, born to a woman he kept in secret for years. I go now to make what amends I can for his sins — and my own.”

That was the last Charleston would see of Josephine Caldwell.

Secrets Uncovered

When Howard’s study was eventually reopened, the contents revealed more than anyone could have imagined. Ledgers, letters, and financial records detailed payments to Tobias Green, the plantation owner who had sold Sarah. The money had secretly supported a woman and child hidden from public view — Howard’s clandestine family.

A partially completed letter in Josephine’s desk, likely written the night of Howard’s death, suggested a darker intent:

“Did you think I would not find out? The girl, the lies, the money — all of it. The tonic I added to your evening brandy will—”

The ink ran, leaving the letter unfinished, yet hinting at poison and betrayal.

A New Life in Boston

Records from Boston in the 1840s identify a Josephine Brown, seamstress, living quietly with a ward named Sarah Winters. Their ages, addresses, and Southern origins matched perfectly with the fleeing women. Under the care of Dr. James Morrison, Sarah recovered from tuberculosis, while Josephine devoted herself to her welfare, selling jewelry and personal treasures to fund her care.

For over two decades, Josephine and Sarah lived modestly, donating small sums to abolitionist causes and never speaking of the past. Sarah passed away in 1867, and Josephine followed shortly after. They were buried together under a single gravestone, bearing the names Sarah Winters and Josephine Brown, with the simple inscription:

At Peace.

Fragments of a Hidden Past

Over the years, pieces of their story resurfaced. A journal, believed to be Josephine’s, surfaced in 1968 at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Its final entry read:

“They will find us together, as perhaps we were always meant to be. I have spent twenty-five years atoning for a moment of rage — for the poison in Howard’s cup. Sarah knew, I think. Yet she stayed. I buried the ring with her yesterday. May it bring her more peace in death than it ever brought in life.”

Dr. Morrison’s notes corroborated some details, including a cryptic mention that Sarah had received the family ring before Howard’s death. The gold signet, engraved with the Caldwell crest and motto Veritas in Tenebris — “Truth in Darkness” — vanished from records, yet its symbolism remains powerful.

Legacy and Mystery

The Caldwell House on Church Street still stands today, admired by tourists unaware of the dark history it conceals. Some claim the air inside the old study remains unnaturally cold, and that faint melodies of a piano occasionally drift through the halls. Whether Josephine was a woman seeking vengeance or redemption, her actions reveal a complex morality shaped by love, grief, and the pursuit of justice.

Her story is not merely one of scandal but of humanity — capable of rage, guilt, compassion, and enduring love. The gold ring that once adorned a young girl’s neck became more than an artifact; it symbolized a truth that refused to remain buried, a circle with no beginning and no end, echoing through the centuries.